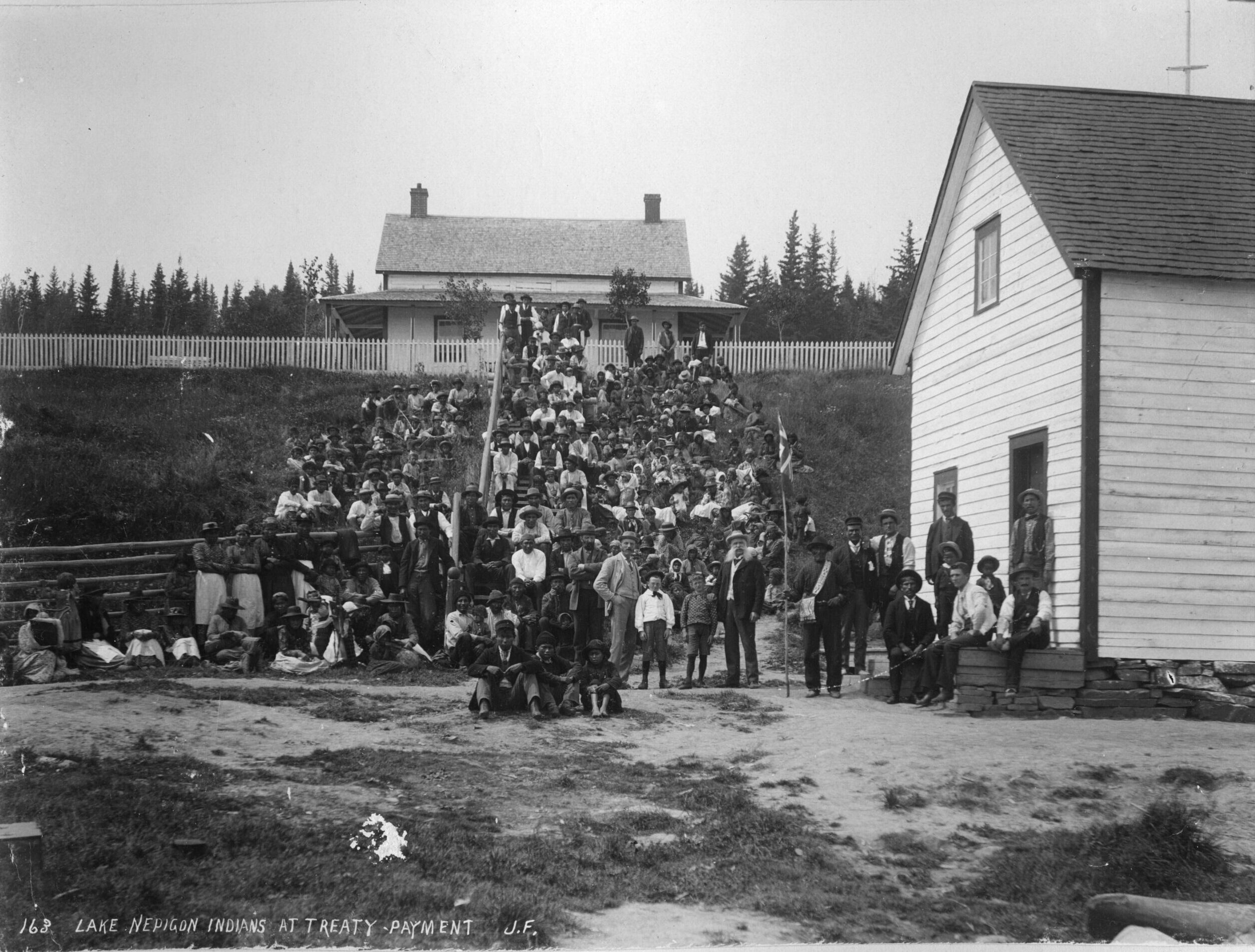

The Thunder Bay Museum is situated on the traditional territory of the Anishinaabe peoples of Gitchi-Gami (Lake Superior) and closest to Anemki-Wajiw (Fort William First Nation) within the treaty area of the Robinson-Superior Treaty of 1850. The Museum’s geographical mandate in Northwestern Ontario also encompasses portions of Treaty #3, Treaty #5, and Treaty #9.

To find more information about treaty areas across Turtle Island and beyond, please visit native-land.ca.

Robinson Superior Treaty of 1850

In the mid-19th century, the Anishinaabe living around the shores of Gichi-Gami (Lake Superior) grew increasingly concerned as mineral exploitation by colonial interests was expanding. This tension culminated when several hundred Anishinaabe and Métis, led by Chiefs Oshawano, Shingwauk, and Nebenaigoching, travelled to the Pointe aux Mines north of Sault Ste. Marie, to convince the Quebec and Lake Superior Mining Association to stop operating. This event, which forced the closure of the mine, became known as the 1849 Mica Bay Incident.

As a result, the government was compelled to seek an agreement urgently, and William Benjamin Robinson was appointed commissioner to negotiate these agreements. The Robinson-Superior Treaty was signed on September 7, 1850, in Sault Ste. Marie, alongside the Robinson-Huron Treaty. This agreement encompassed the Lake Superior watershed from Batchawana Bay to the Pigeon River and set aside reserves, including Anemki-Wajiw (Fort William First Nation) and many other communities along the north shore of Lake Superior.

The terms of the treaty included the issuance of ongoing annuity payments and guarantees for the continuance of hunting and fishing rights in the treaty area. This treaty established a framework for the ‘treaty system’ that would govern relations between Indigenous peoples and the government, providing a model for the ‘Numbered Treaties’ that followed.

Treaty #3 and Adhesions

Beginning in 1869, as the Dawson Trail, a land-water route from the Lakehead to the Red River Settlement, began to be developed, the Anishinaabe in that area petitioned the government with requests in exchange for the use of their land that would enable a right-of-way for the route.

Following years of stalled negotiations, Treaty #3 was eventually signed on October 3, 1873, at the Northwest Angle on Lake of the Woods, covering a vast area that now comprises Northwestern Ontario and eastern Manitoba. The underlying causes of the delay included the conflict between the Métis and the Crown (1869–70), which reshaped prairie politics and compelled Ottawa to negotiate the Manitoba Act (1870), recognizing Métis land rights in principle and creating the province. These events heightened the federal urgency to secure transportation corridors and access to resources westward, directly informing the Crown’s stance in the lead-up to Treaty 3.

The primary negotiators and signatories for the Anishinaabe were Chief Mawedo-peness from Rainy River, Powassin (Pow-wa-sang) from Lake of the Woods, Chief Blackstone of Lac des Mille Lacs, and Chief Sah-Katch-eway from Lac Seul. They were working with Alexander Morris, the recently appointed Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories, and acting as the lead Commissioner and representative of the Crown during the negotiations.. This sacred agreement was negotiated through ceremony and traditional customs, which emphasized its spiritual and political significance.

While Treaty #3 affirmed certain rights of the Anishinaabe, the Crown often failed to uphold its promises. As settlement and resource extraction increased, Indigenous communities were faced with the chilling reality of the agreement with the Crown. Government policies and projects such as the Canadian Pacific Railway, which expropriated traditional lands, caused irreparable harm to communities and effectively undermined the treaty relationship. Following the signing, the Shebandowan Adhesion (13 October 1873), and Lac Seul Adhesion (9 June 1874) were negotiated for communities unable to attend, as well as the Half-Breed Adhesion (12 September 1875), which pertained to Anishinaabe of mixed ancestry in the Rainy Lake/Rainy River area.

Courtesy of The Muse: Lake of the Woods Museum & Douglas Family Art Centre.

We graciously thank the Muse: Lake of the Woods Museum & Douglas Family Art Centre for providing information and images for Treaty #3 in this exhibit.

Treaty #5

In the mid-1870s, the Omushkegowuk and Anishinaabe peoples living around Lake Winnipeg began advocating for an agreement that would offer protection from the encroachment of colonial interests, being aware of similar provisions that had been provided in previous Treaties #1 through #4. Initially, the government showed little interest as these prior treaties had already secured the agricultural belt to the west. However, as interest in the land surrounding Lake Winnipeg increased, the government was swayed to pursue this new treaty.

Treaty #5 was signed in 1875-76, encompassing much of present-day Manitoba, portions of Saskatchewan, and a portion of Northwestern Ontario. While Treaty #5 was modelled on previous treaties, its terms are less generous. While the freedom to hunt, trap, and fish on undeveloped surrendered lands was retained, individual annuity payments and the formula for determining reserve lands were substantially smaller.

Several adhesions to Treaty #5 were signed in northern Manitoba between 1876 and 1910, following its initial negotiations. Today, Treaty #5 encompasses the Ontario communities of Pikangikum, Poplar Hill, Deer Lake, Sandy Lake, and North Spirit Lake.

Treaty #9 and Adhesion

The Omushkegowuk and Anishinaabe living within the Hudson’s Bay watershed had contacts with signatories of the Robinson-Superior Treaty, which guaranteed hunting and fishing rights to Indigenous communities on the shores of lakes Superior and Huron, and believed a similar treaty could secure protection over their land. In the latter part of the 19th Century, pressures of mining, forestry, commercial activities, and hydroelectric development had risen in the Moose River basin, leading to concerns about losing their traditional way of life for Indigenous communities.

The James Bay Treaty, also known as Treaty No. 9, was signed in 1905-1906 in Ontario, covering large portions of the James Bay and Hudson Bay watersheds, which comprise two-thirds of the province’s total land area. It covers 14 First Nations and various communities, including Kapuskasing and Hearst. The treaty is the northernmost treaty in Ontario, with adhesions added in 1929 and 1930 that extended its reach from the Albany River to Hudson’s Bay.

Since its signing, Elders from the signatory Nations have advocated for changes to the written document as it did not accurately reflect the oral agreements between them and the commissioners. Exploiting the Hudson Bay Watershed’s hydroelectric potential has also been a source of tension since the treaty’s signing, as these developments have profoundly impacted hunting and fishing on the land.

Further Resources

The James Bay Treaty (Treaty No. 9). Online Exhibit – Archives of Ontario

The James Bay Treaty (Treaty no. 9) – Archives of Ontario

Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905

By John Long

(available in the Museum’s library)

This is Indian Land: The 1850 Robinson Treaties

Edited by Karl Hele

(available in the Museum’s library)

Responding to White Encroachment: The Robinson-Superior Ojibwa and The Capitalist Labour Economy 1880-1914

By Steven High,

Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society Papers & Records XXII (1994), 23-39.